BACK

Dec 10, 2025

UAV Prototypes (2022–2026+)

2025-12-11: Edited for clarity.

Why

I began this pursuit with zero background knowledge, as a high-school student who had a little too much time and curiosity.

Five years ago, my spare time was often invested in an engineering sandbox videogame (to the tune of ~1000 hours). Through the game, I gradually unearthed a passion for learning via trial and error; without fail, it was immensely rewarding every time an ever-more complex vehicle finally worked, following a dozen hours of debugging and redesigning. After a year, this personal satisfaction led me to ponder, admittedly with a hint of overzealousness: why not direct my effort towards achieving the same things, but in real life? At the time, I was cognizant that the technical aspect would not carry over, and that actual physics would be exponentially harsher (albeit less glitchy). However, I firmly believed one thing, which is that the fundamental problem-solving would be the same, while the impact far more tangible...

I’ve yet to change my mind.

Vision

My desire in 2022 was to see a fixed-wing drone fly before my eyes. Over time, however, I’ve inevitably shifted my self-imposed goalposts. As it stands, my effort is focused on iteratively inching closer to the deployment of a multi-vehicle IoT ecosystem (land/air). However, the core objective of this project has remained the same: to be a platform for growth, both of my project management and technical skills. Throughout 2026, the learning outcomes I seek range from higher-fidelity CFD validation and topology optimization to custom PCBs and IoT & autonomy integration.

Nascent Prototypes (2022-2024)

Prototypes produced with the primary objective of exposing required concepts, skills, and considerations required for small-scale UAV development.

BLZN-1

Design

Core development ran from October 2022–March 2023, with the only flight test occurring in August of 2023.

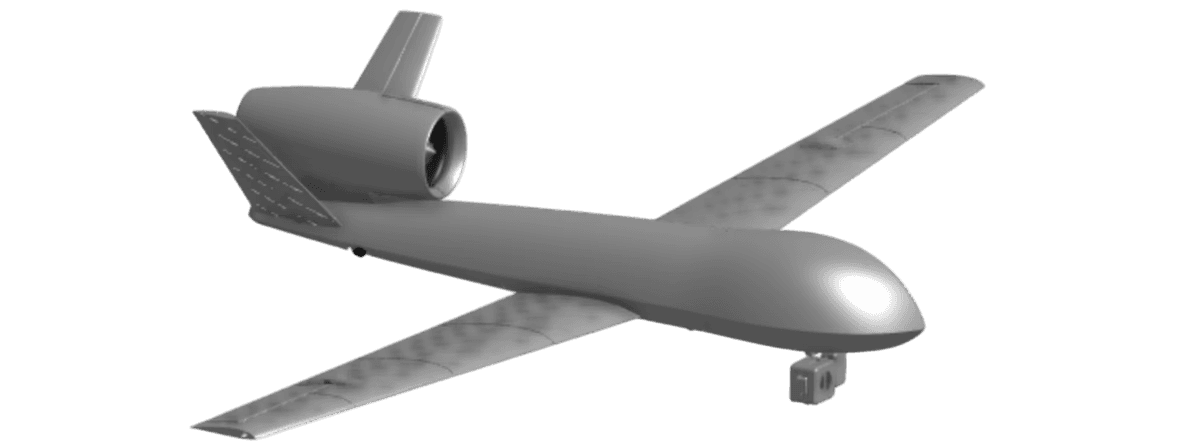

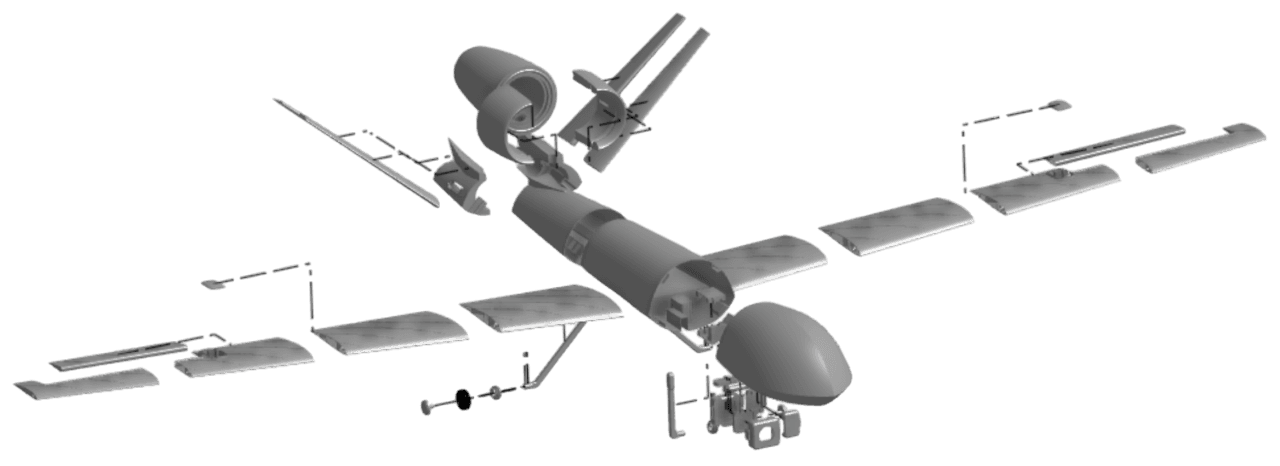

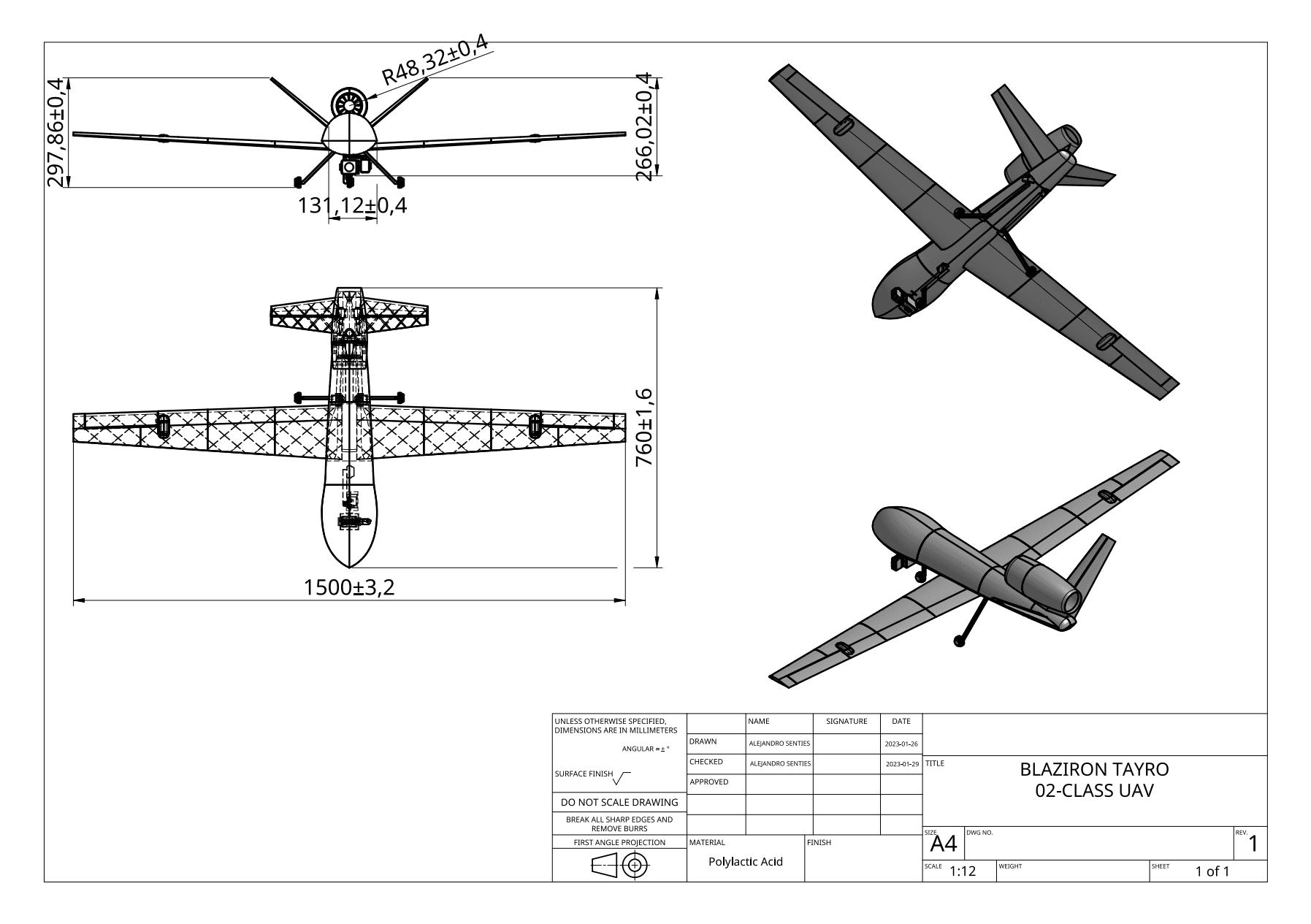

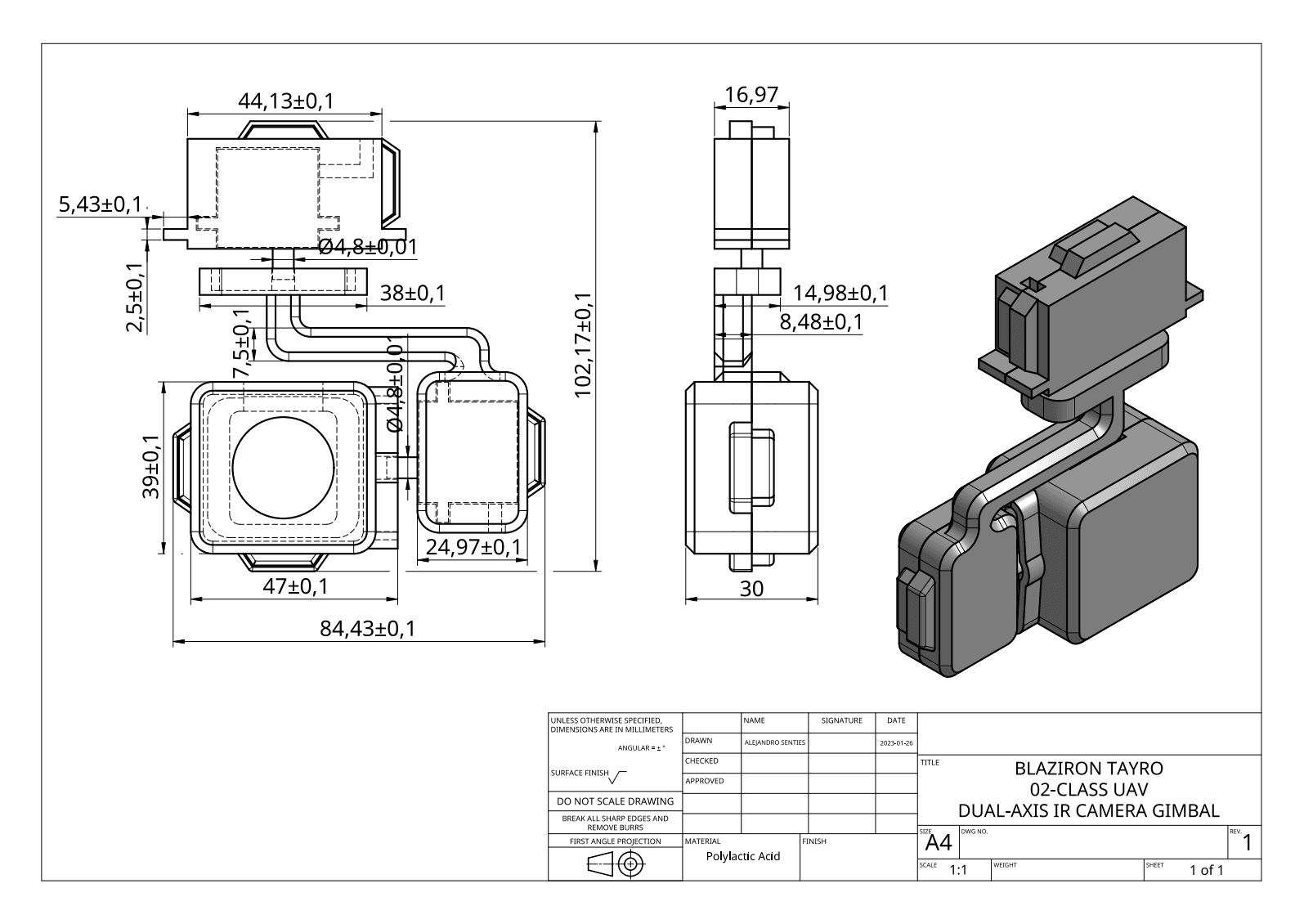

The first attempt had a relatively simple fixed-wing architecture, with a 150 cm / 59 in wingspan. A single, 70 mm rear EDF mounted between a v-tail would propel the aircraft, which had retractable landing gear and a dual-axis camera gimbal. The airframe was fully printed out of PLA filament, with thin carbon-fiber spars running through the wings, and a thick shell for rigidity.

Outcomes

The aircraft crashed immediately upon hand-launching (which was necessary as the landing gear was not suitable for the aircraft weight). The key flaws that sealed the fate of the aircraft were the lack of CFD validation, an excessive weight (and fluctuant at that, due to no internal fastening of avionics), poor structural design (minimal load distribution within the fuselage structure due to a lack of ribbing and surface area for inter-part adhesives), and little design consideration given to repairability. The aircraft was rendered unrecoverable after the crash, and was never rebuilt. A meticulous analysis of the design and manufacturing flaws was performed and documented.

The lessons/achievements that persevered for future iterations were the functional configuration of the core RC avionics, and CAD considerations for manufacturing.

BLZN-2

Design

The development ran from December 2023–March 2024, with initial hover testing occurring in March of 2024.

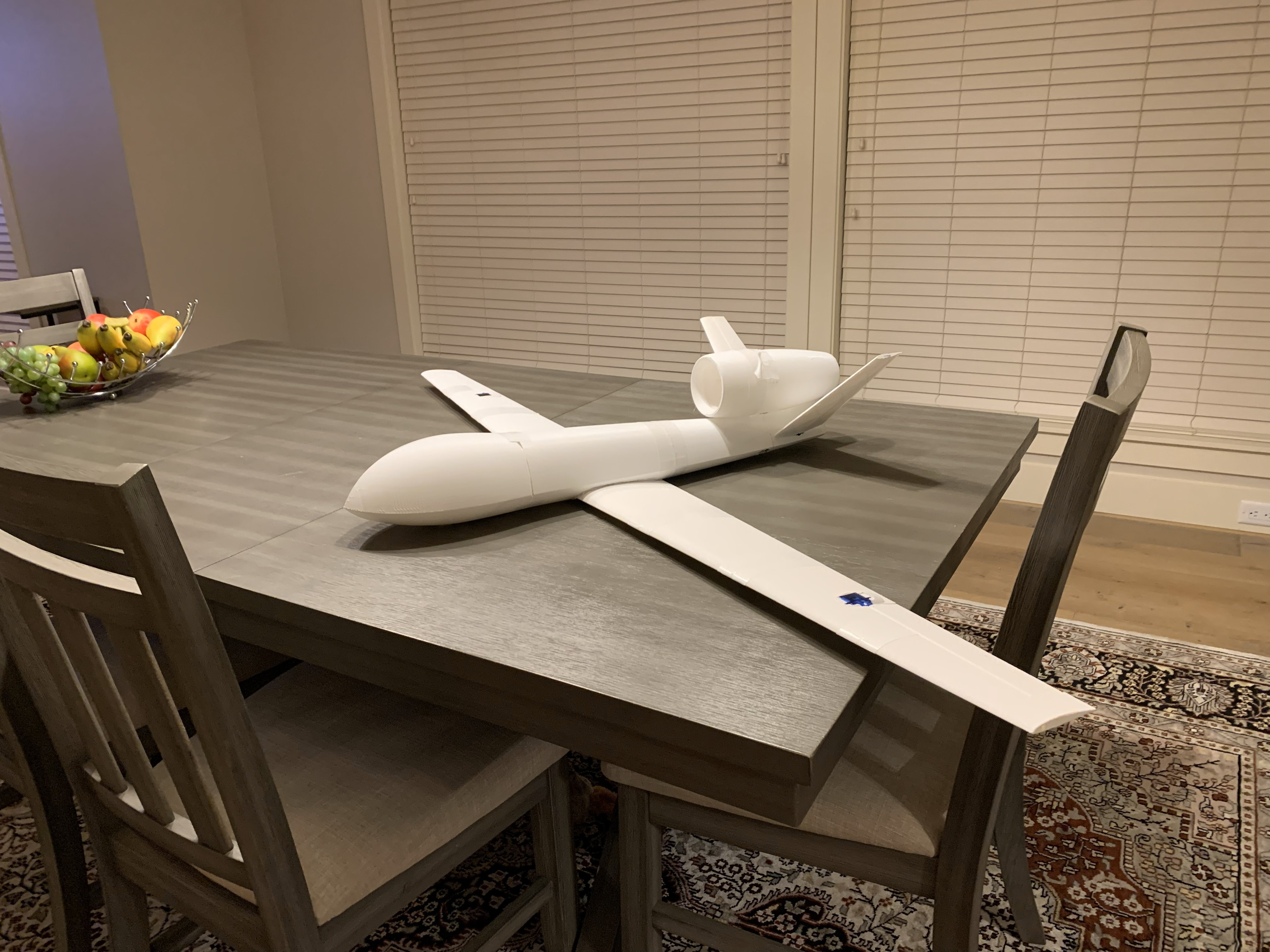

The second aircraft was designed as a hybrid VTOL/fixed-wing platform, intended to ameliorate the flight-testing hindrances imposed by BLZN-1’s fixed-wing design. It had an 80 cm / 31.5 in wingspan, and improved the historical structural shortcomings by eliminating avionics movement, poorly distributed loads and the need for conventional landing gear, opting for reinforced inverted winglets and an inverted v-tail as landing struts. The propulsion layout was inspired by the Harrier jet’s 4-post nozzle layout, and the aircraft was powered by a high-performance (+44% static thrust vs. BLZN-1) 70 mm EDF.

Outcomes

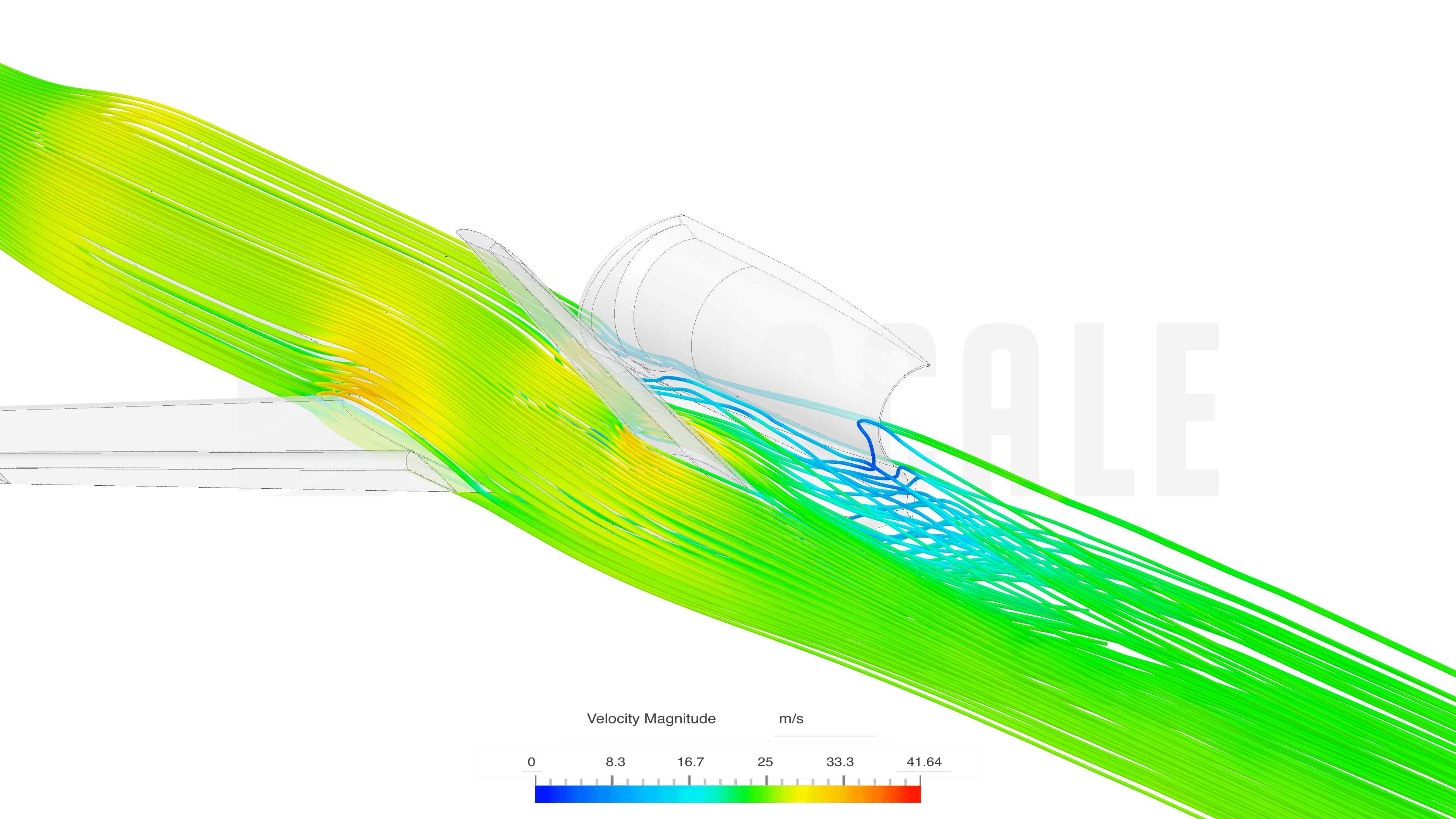

The aircraft was incapable of fully lifting off of the ground, despite the high-performance EDF. Fatal flaws with the aircraft comprise the inefficient ducting (intake design and internal routing), excessive friction between the fuselage and pivoting nozzles (which inhibited high-speed nozzle positional corrections), and theorized ground effect and/or CG factors.

The aircraft succeeded, however, in consolidating optimal 3D-printing practices with regard to tolerancing, surface finish, and weight estimation, in addition to exploring rudimentary CFD simulation. It also taught me about dimensional insimilitude, and how the curvatures of my ducting (and lateral distances for hover roll authority) would have to be distinct from that of larger models (& the Harrier itself) for the 4-post layout to be effective.

BLZN-3

Design

The development was completed during April of 2024, with hover tests occurring 17 days after those of BLZN-2.

The VTOL-only airframe was intended as a low-sophistication testbed to investigate the effects of internal ducting on the static thrust output of the vehicle, compared to the free-stream values of the EDF. The design had no functional fixed-wing elements, comprising only a structure for avionics, ducting, and the EDF, with the wings from BLZN-2 attached to better approximate a real moment of inertia for a hybrid aircraft of that scale. The ducting layout was a 3-post instead of 4, but other dimensions remained similar.

Outcomes

The aircraft was incapable of taking off, exhibiting similar behavior to BLZN-2. The testbed was able to produce more torque about its center of mass, but this is probably a result of its comparatively reduced weight rather than an increase in ducting efficiency.

BLZN-C4

Design

The development ran from April to May of 2024, with initial manufacturing occurring in August 2024.

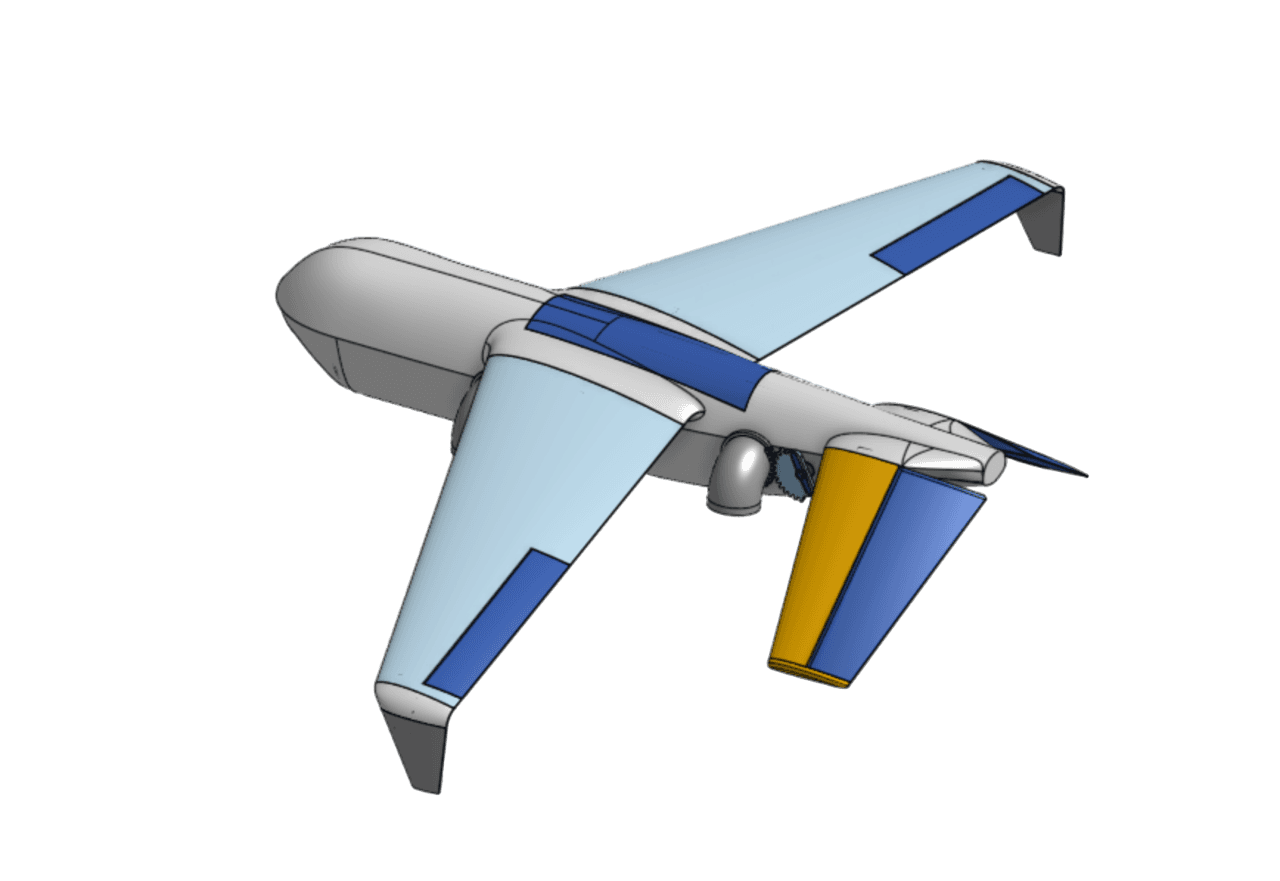

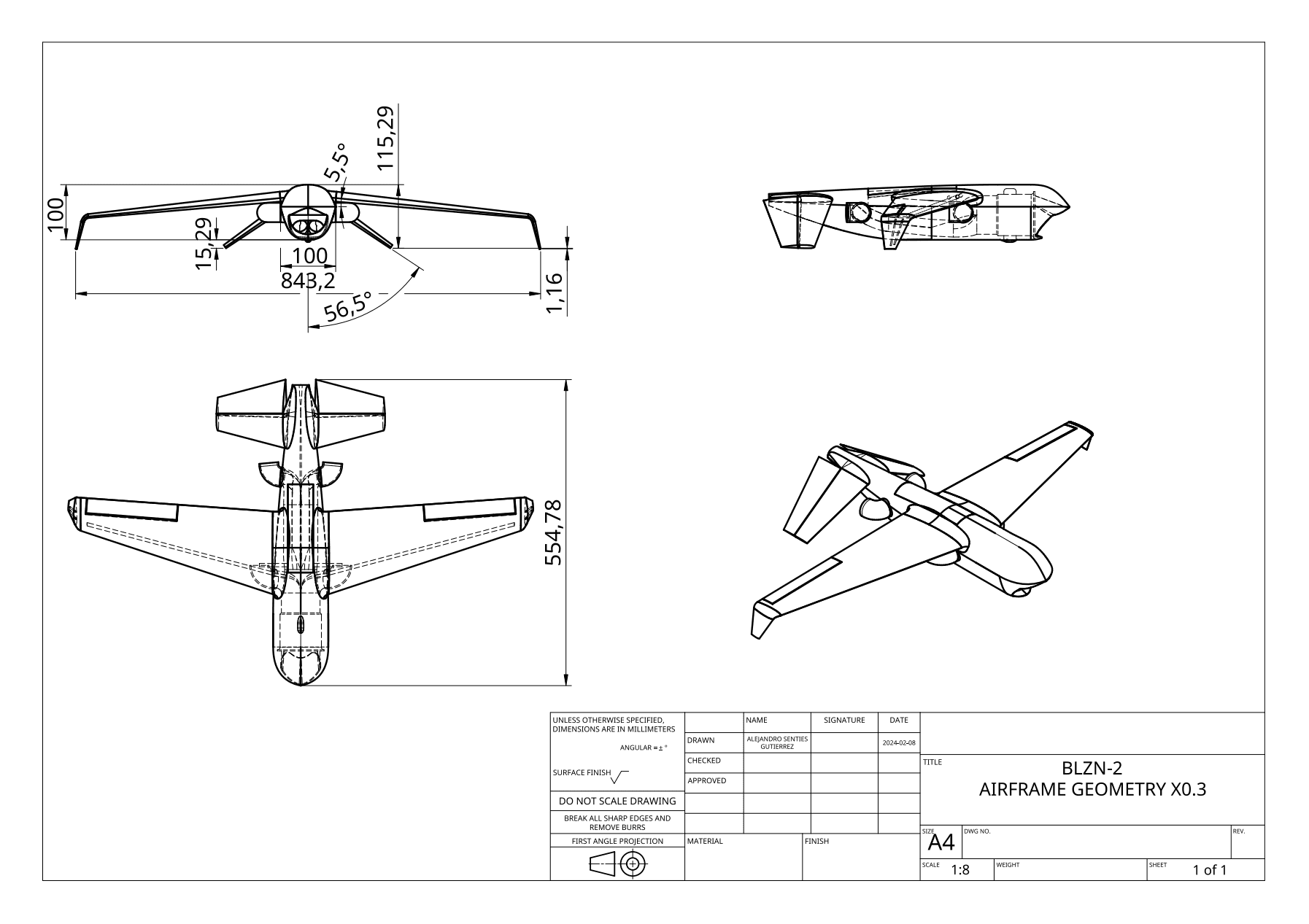

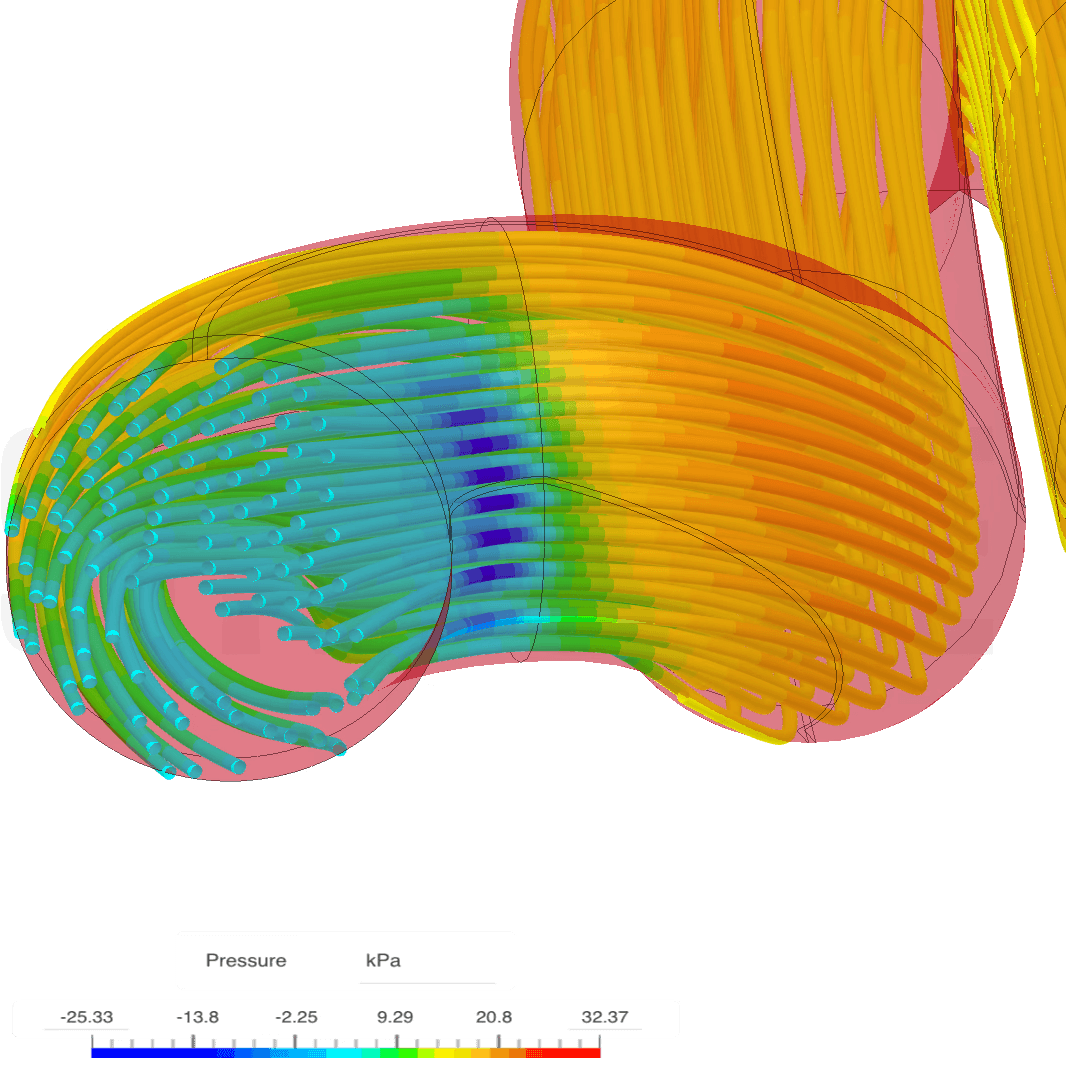

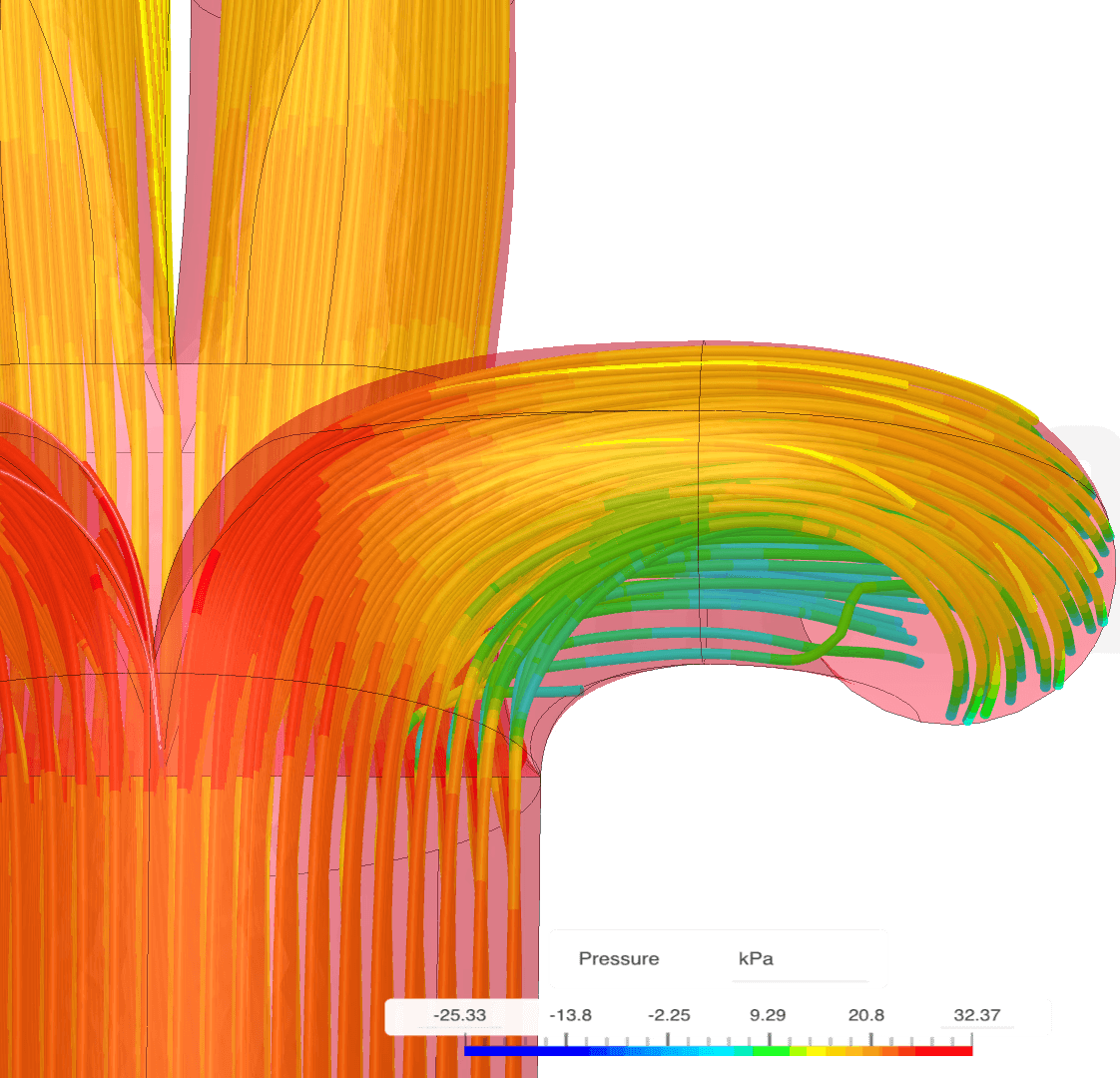

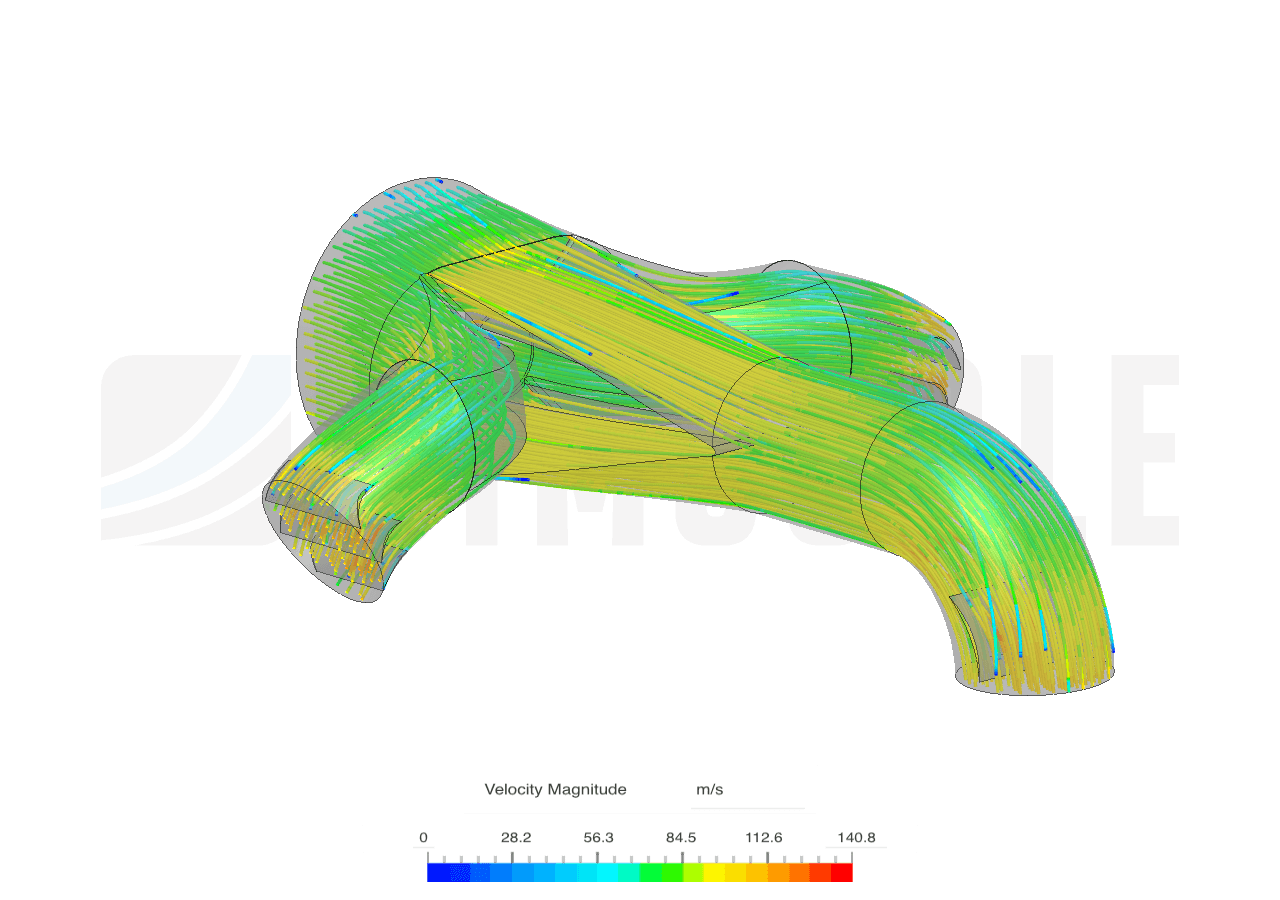

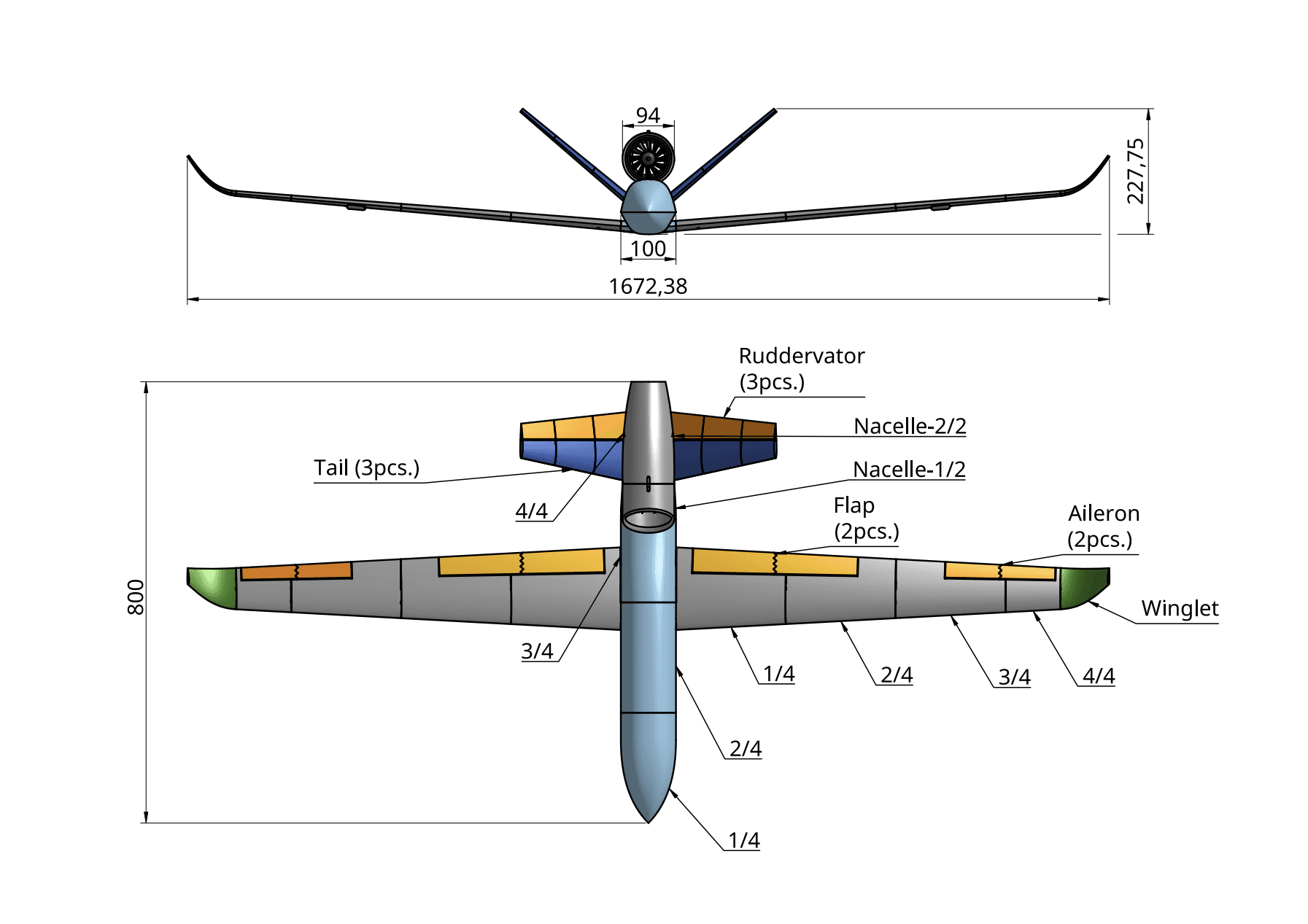

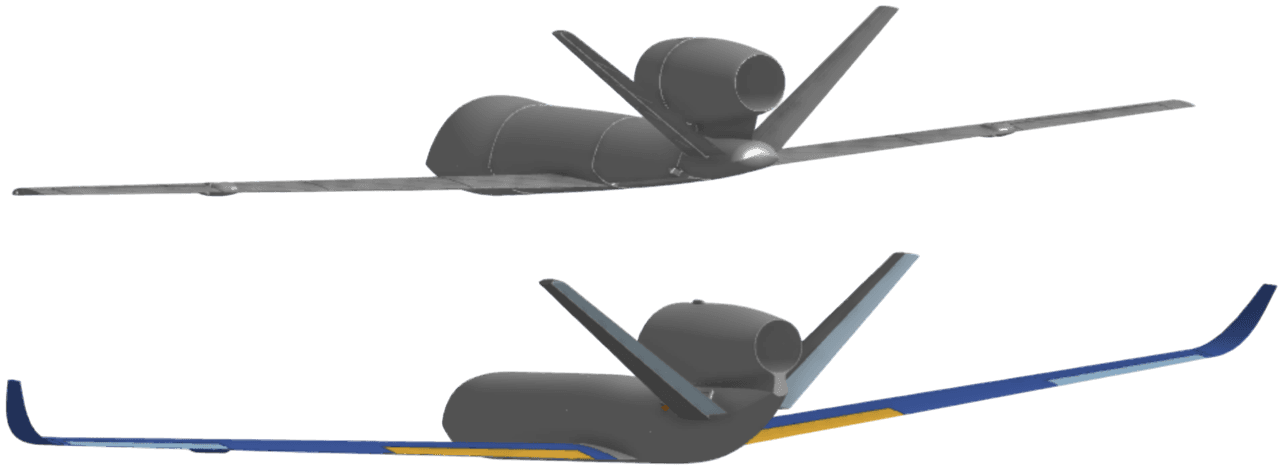

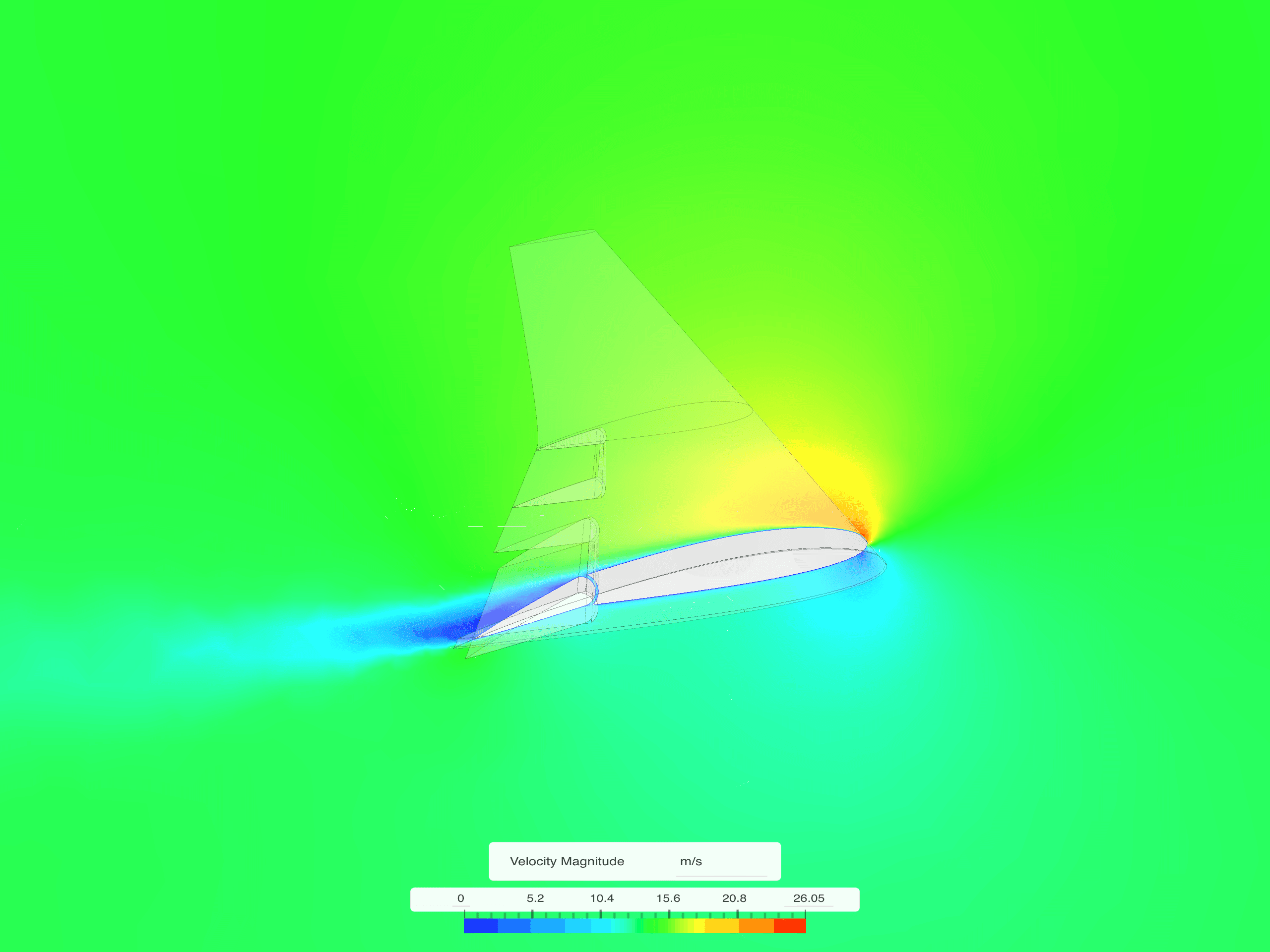

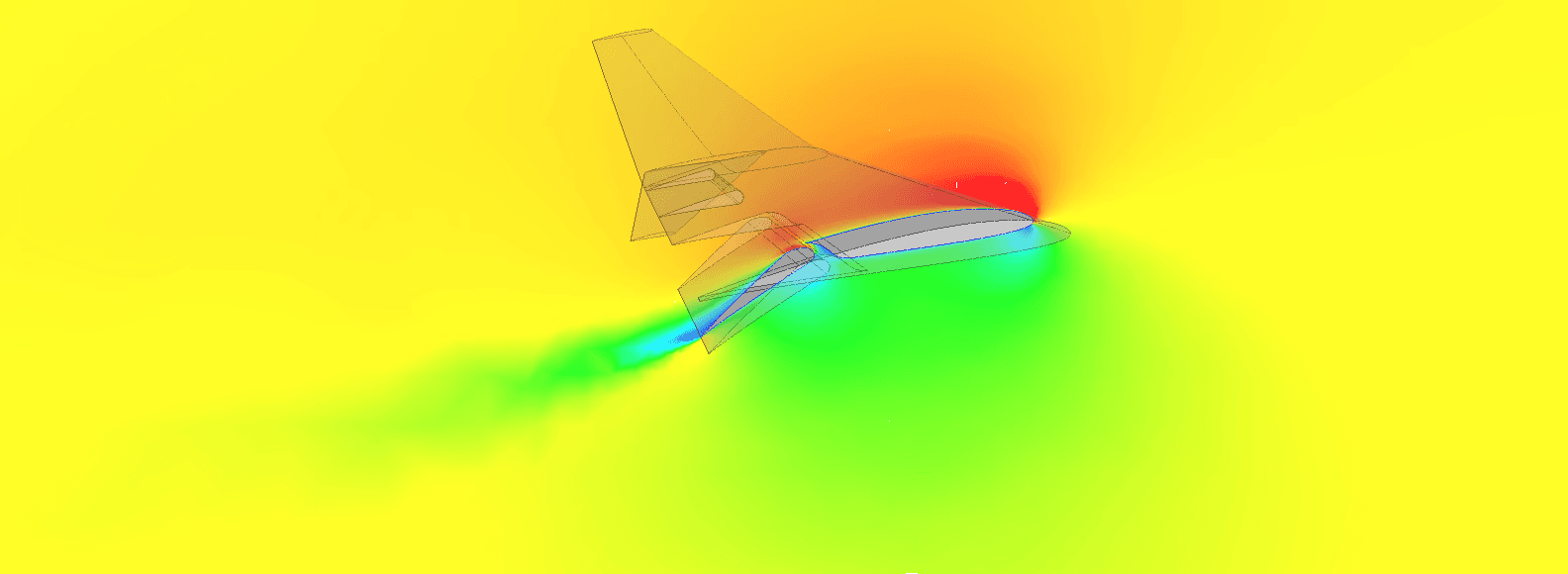

The airframe was intended to be one of two airframes, designed for a future integration. The “H” variant would be VTOL, the “C” would exclusively be CTOL. With a 150 cm / 59 in wingspan (excluding winglets), the aircraft was designed to have increased thrust and a reduced projected frontal area than the prior BLZN-1, incorporating all the manufacturing and structural best-practices since learned, in tandem with complete CFD validation prior to manufacturing. Contrasted with BLZN-1, the aircraft had a higher aspect ratio v-tail, a longer rear-EDF nacelle, a more efficient wing airfoil, winglets and no camera gimbal for reduced drag, large flaps, and superior landing gear structures (& landing gear doors). CFD was employed to optimize the angle of incidence, flap sizing and maximum deflection, winglet shaping, and trim flight angles for the ruddervators.

Outcomes

A couple of non-negligible aerodynamic concerns included the low pressure zone that would form towards the aft of the EDF nacelle, and the lack of simulations performed which accounted for landing gear, and its effects on the net pitching moment and total drag. Regarding the physical prototype, the airframe was never fully manufactured due to printing difficulties with lightweight foaming PLA, in addition to a lack of design emphasis on manufacturability.

A practice that persevered for future iterations was the employment and interpretation of CFD for more extensive aerodynamic validation, which allowed for problematic design elements to be identified and addressed early on. Additionally, despite difficulties faced with the selected LW-PLA filament, the experimentation demonstrated that (with adapted DFM considerations) specialized materials could be implemented for superior strength-to-weight ratios.

Autonomous Prototypes (2025+)

Prototypes produced with the primary objective of exposing required concepts, skills, and considerations required for UAV autonomy and swarms. A collateral objective is to provide additional opportunities to apply more rigorous structural and aerodynamic optimization techniques.

BLZN-5

Design

The development began in December of 2024, and saw sporadic progress in July 2025 and December 2025. VTOL testing is expected in January 2026, with forward-flight testing subject to the VTOL and mechanics success targets reached.

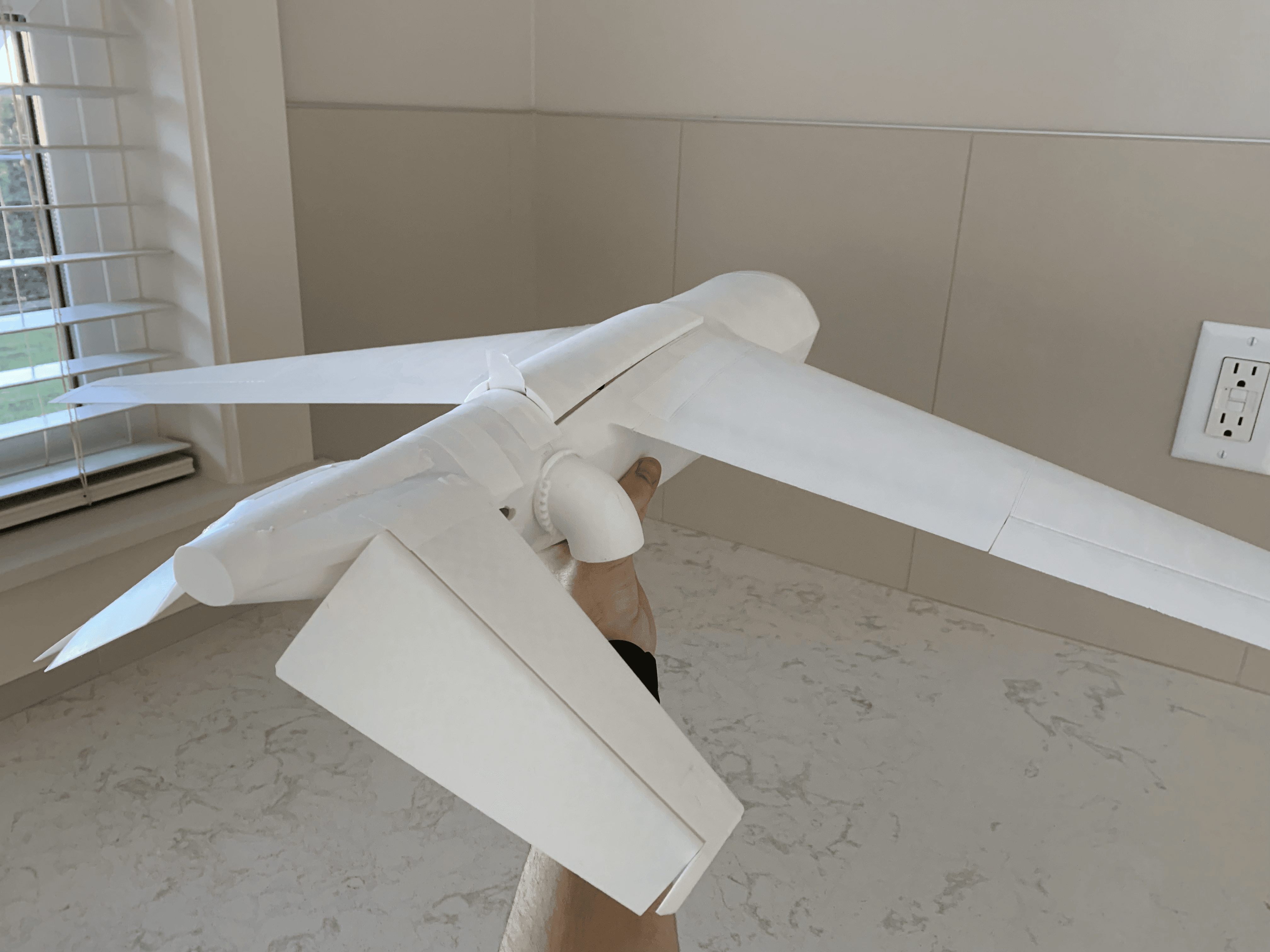

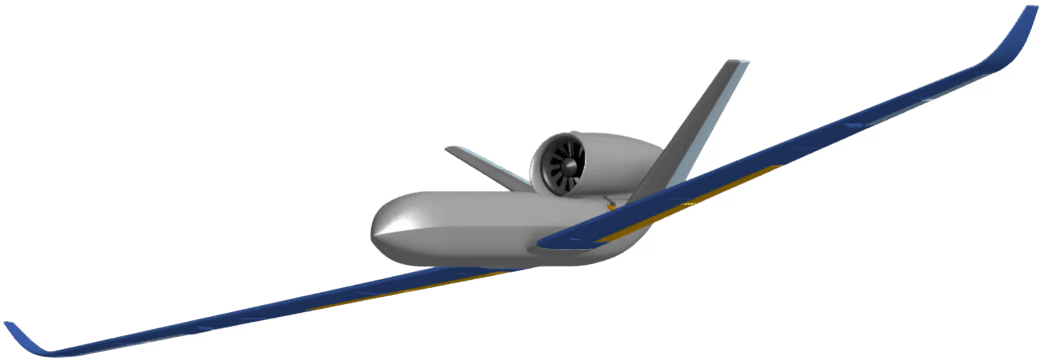

The fifth design is an attempt to methodically integrate both prior lessons and novel techniques into the aircraft. Its wingspan will remain equivalent to BLZN-C4’s (150 cm / 59 in), while bringing upgrades such as slotted flaps and split winglets. For hybrid VTOL/CTOL capabilities, an inverted tri-copter layout (with the two rear EDFs tilting) was chosen, with thrust-vectored EDFs (two external and one internal, a decision informed by the inefficacy of internal ducting seen in BLZN-2 & BLZN-3). FEA analysis will be conducted and compared with real-world deflection tests, to allow the design to best utilize advanced materials such as PET-CF for load-bearing frame components, and special PLA or ASA variants for aircraft skin and fine mechanical components. The approach to internal structures is completely distinct to any previous iteration, comprising a full carbon-fiber frame and topology-optimized structures for skin ribs. A complete CFD analysis will dictate design changes to ensure dynamic stability and control-surface authority, in addition to static stability analyses performed as with BLZN-C4.

Notably, prior aircraft only possessed basic battery voltage telemetry through a receiver implement. The addition of a dedicated flight controller and power-distribution board will enable detailed data logging, in addition to introducing capability for autonomous missions. These tools will facilitate PID tuning and real-world aerodynamic validation of CFD results. The airframe will also be designed for easy repair and upgradeability, by superseding the prior reliance on permanent cyanoacrylate bonds with screw-based assembly.

Outcomes

Pending manufacturing.

More